Social Impact by Empowering Ivorian Artists Through Philosophy

Creating an Intersectional Lens

I designed the course around the idea that visual literacy is much more than technical skill—it’s about sensing and telling stories that are layered with meanings of race, gender, colonialism, class, and sexuality. Drawing inspiration from thinkers like Frantz Fanon and Achille Mbembe, I explained that philosophy can provide us with “tools” that enable us to see the world in its full complexity. For example, Fanon’s passionate call for art as “combat literature” reminded us that photography can be a weapon of resistance. In this way, I showed my students that their work wasn’t merely about capturing images, but about engaging with power structures and imagining new narratives.

This idea resonated with many artists globally. Recent examples in decolonial pedagogy—such as exhibitions and workshops that centre on the interplay of identity and power—have shown that when philosophy meets art, it can unlock hidden dimensions of social critique and transformation. For an idea of this type of work at the museum, please take a look here.

Artists & Philosophy Education

African photographers need more access to educational opportunities to develop their storytelling skills. These include important skills related to visual literacy and an intersectional sensibility that help photographers recognize/sense/feel, and tell stories with multiple intersecting layers. Such layers include crucial dimensions of race, gender, colonialism, class, and sexuality. Telling such stories, therefore, requires an intersectional lens or sensibility, an approach that considers how various axes of identity can reinforce marginalization (Crenshaw, 1989, 1990; Al-Faham, Davis & Ernst, 2019). This includes the vital connection between visual literacy and philosophical sensibility because intersectionality applies to narratives and how they allow for complex storytelling, especially as it helps to question the relationships between identities, social-political positions, and philosophical concepts and how this may lead to transformation (Nash, 2008). As the feminist philosopher Ann Gary explains: “It provides a framework or strategy for thinking about issues, a set of reminders to look at a wider range of oppressions and privileges to consider their mutual construction or at least their intermeshing (if these are different).” Artists like photographers with the right conceptual-affective tools and better able to see these layers and express them through their work are crucial because, as the visual-first media organization Catchlight (2018) emphasizes: “Visual storytellers have a vital role in keeping people informed, promoting community awareness, encouraging civic engagement, and leading change as visionaries.” With this in mind, the aim is to cultivate photographers’ visual literacy skills with a sensibility to intersectional narratives and the tools necessary for telling stories that lead to change.

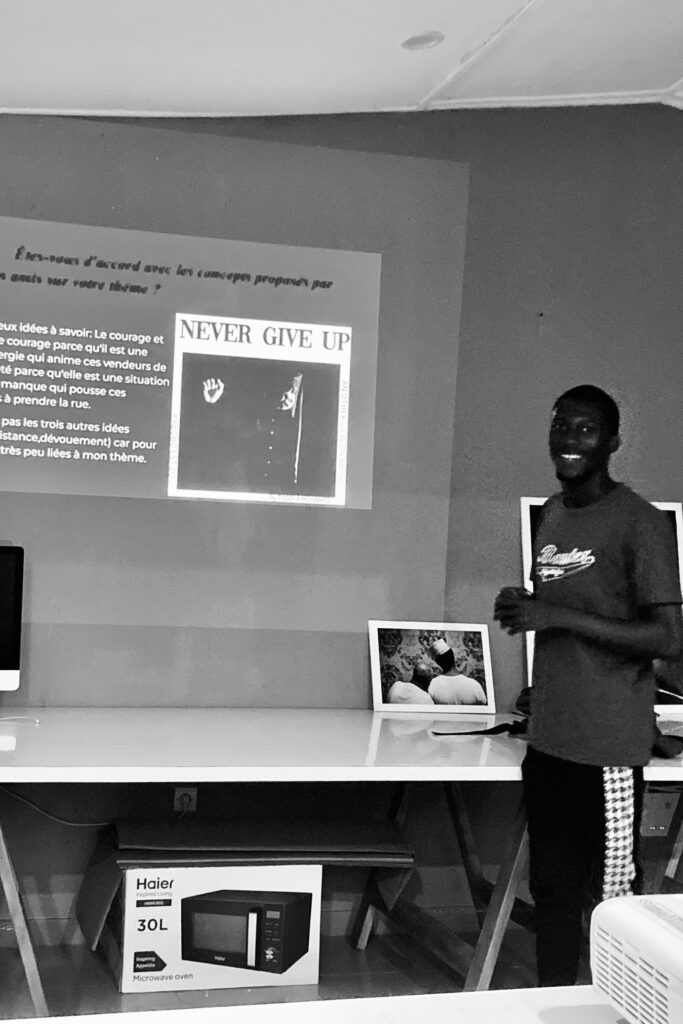

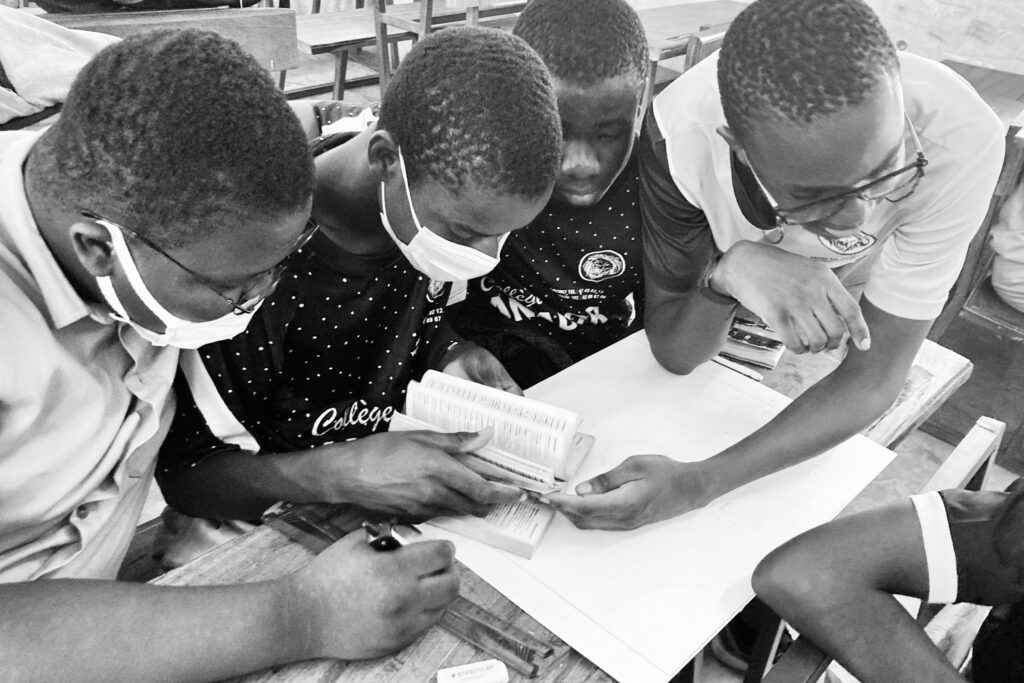

Below, you will find some impressions of the course for these amazing artists.

The term visual literacy rose to prominence in the 1960s, especially through an article by Jon Debes, who worked for the Eastman Kodak Company in Rochester, New York. In the article “Visual Literacy in Education,” Debes (1969) argues for the inclusion of visual elements into education, which paved the way for the visual literacy movement:

Visual Literacy refers to a group of vision-competencies a human being can develop by seeing and at the same time having and integrating other sensory experiences. The development of these competencies is fundamental to normal human learning. When developed, they enable a visually literate person to discriminate and interpret the visible actions, objects, symbols, natural or man-made, that he encounters in his environment. Through the creative use of these competencies, he is able to communicate with others. Through the appreciative use of these competencies, he is able to comprehend and enjoy the masterworks of visual communication.

Since then, its definition has changed to accommodate new developments. For example, visual literacy now involves reading and writing images (Avgerinou & Pettersson, 2011; Bamford, 2003). With new technologies and an increasingly media-saturated world, the meaning of visual literacy has changed (Postman and Weingartner, 1971) and includes a mix of capabilities (Kedra, 2018). From a psychological perspective, the film theorist and psychologist Rudolf Arnheim (1969) drew on Gestalt theory and described “the discipline of intelligent vision” (p. 307) that can not be isolated from other curricular areas and emphasized that “[v]isual thinking is indivisible” (p. 307). Since then, various efforts have been made to develop and incorporate visual literacy-related theories into education. For example, the cognitive psychologist Abigail Housen developed stages of aesthetic development (Housen, 1980), and Philip Yenawine, the former director of education at MOMA, introduced visual thinking strategies as a pedagogical tool (Yenawine, 2013, 2018; Hailey, D., Miller, A., & Yenawine, 2015) drawing on the work of Jean Piaget, John Dewey, Lev Vygotsky, and Jerome Bruner (for more, see Nolan, 2023).

rom a philosophical perspective, several important visual literacy-related aspects have been highlighted. For example, the changing of perception and interpretation in mass media (Benjamin, 1936), the way images become a ‘spectacle’ and lead to alienation in society (Debord, 1967), the role of semiotics and cultural myths in relation to images (Barthes, 1957), how context shapes perception and interpretation (Berger, 1972), the cultural and ethical implications of taking a photograph (Sonntag, 1977), the becoming ‘hyperreal’ of images or more real than reality itself to its consumers (Baudrillard, 1981), and, finally, a dynamic of power in visual representation that shapes cultural and political discourse (Mitchell, 2006). All these issues involve some form of learning and would benefit especially from a kind of learning that helps to ‘see’ these aspects. The critical theorist Douglas Kellner (1988) writes that “it is precisely the images which are the vehicles of the subject positions and that therefore critical literacy in a postmodern image culture requires learning how to read images critically and to unpack the relations between images, texts, social trends, and products in commercial culture” (p. 43).

Unfortunately, as Schönborn and Anderson (2006, 2010) argue, only a limited amount of pedagogical interventions have been made. A lack of such initiatives also means lacking the potential for social change, and based on the available literature on visual literacy, such interventions are critically important. As the famous neurologist Oliver Sacks said: “Our perception is an active, constructive process that depends on our expectations, our memories, and our ability to reason.” Such ability requires training the visual ‘muscle’ because, as the Nobel laureate Francis Crick (1994) put it, whether you see something rather than nothing depends on your primary visual cortex.

In sum, visual literacy and social advocacy join hands in photography when it critically examines social issues, intersectional perspectives, public perception of truth and ‘fake news,’ visual activism, persuasion, ethical considerations, and educational initiatives. To realize such a critical examination requires rigorous training. To put it in the poetic words of curator Mark Sealy (2022), who compares photography with the improvisational and liberatory qualities of jazz, “we can work towards a more spontaneous and receptive way of thinking that opens up space for sensing and feeling the work that a photograph generates across different individual, temporal and cultural experiences” (p. 2).

A Philosophical Curriculum for Visual Transformation

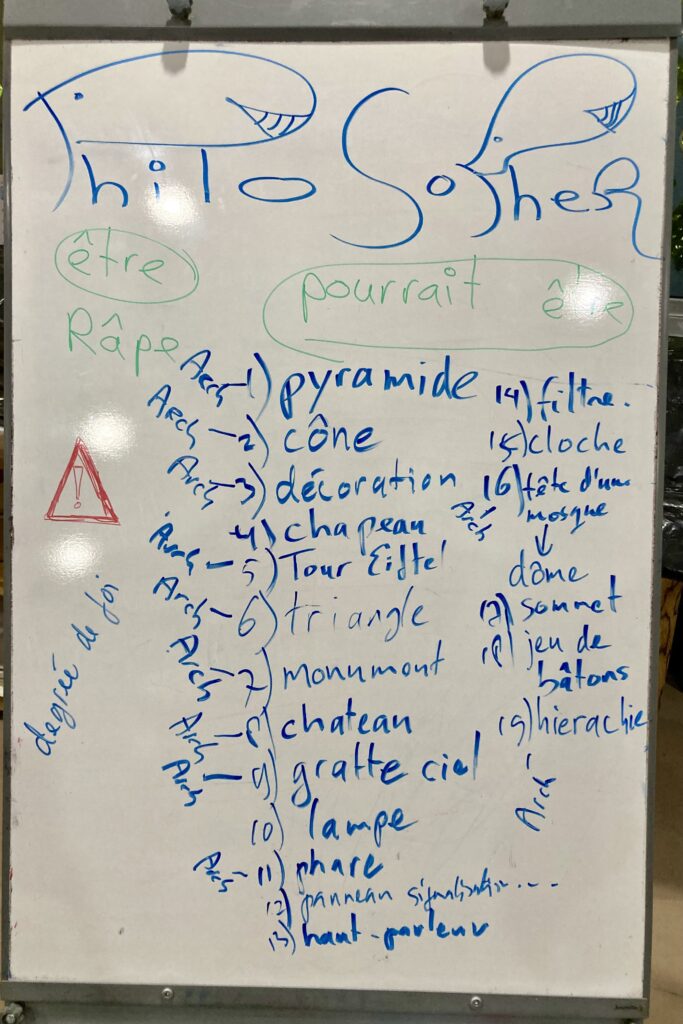

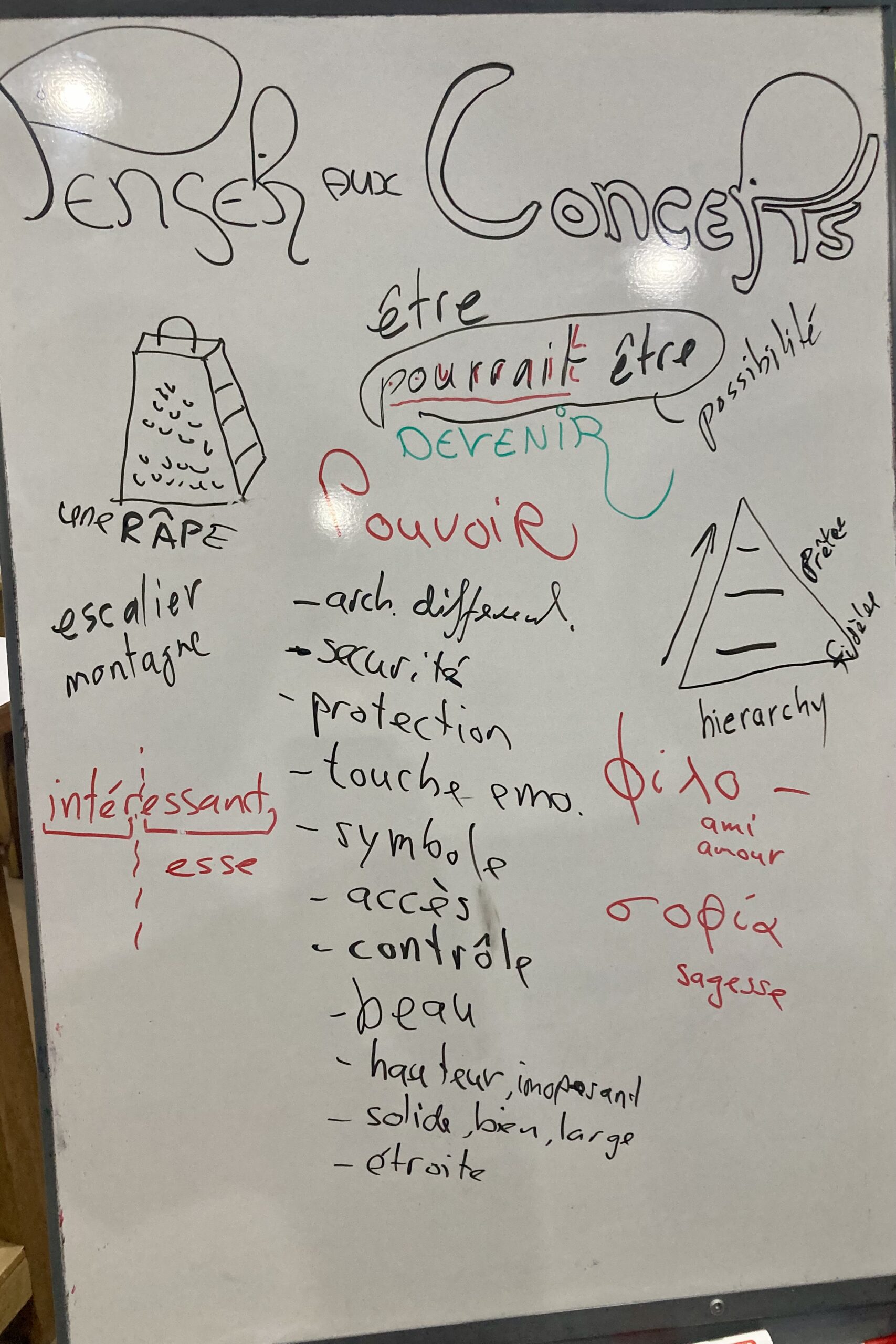

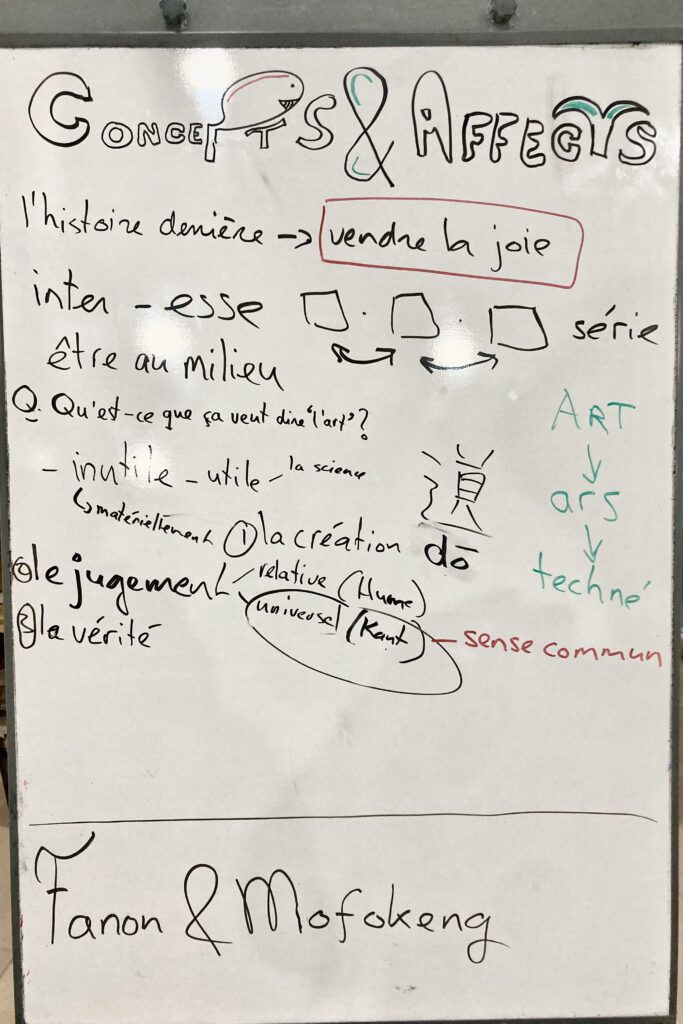

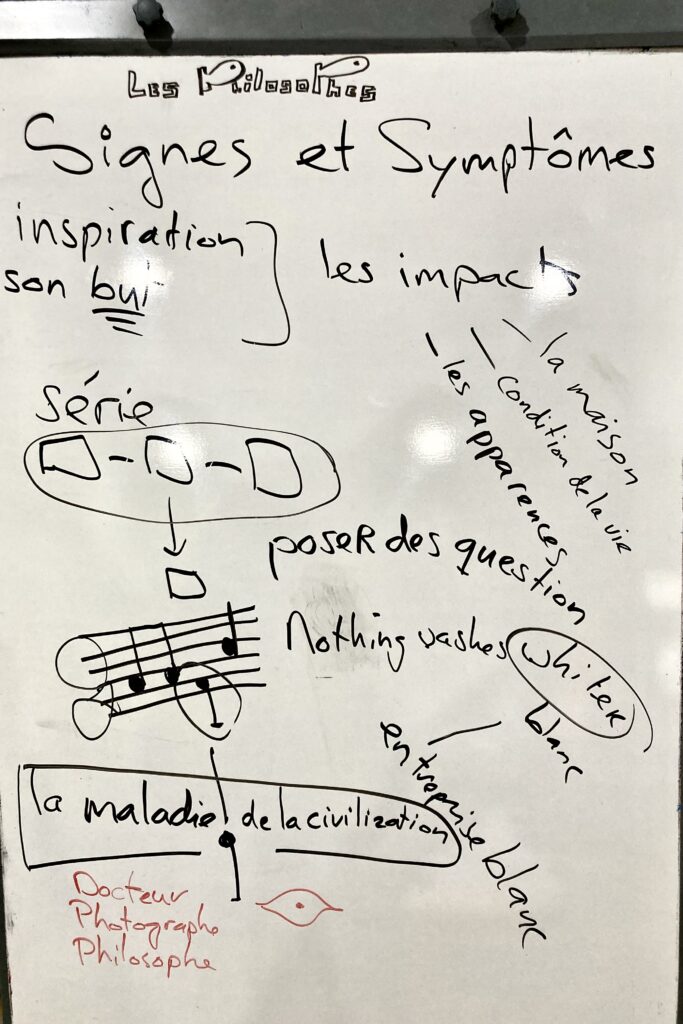

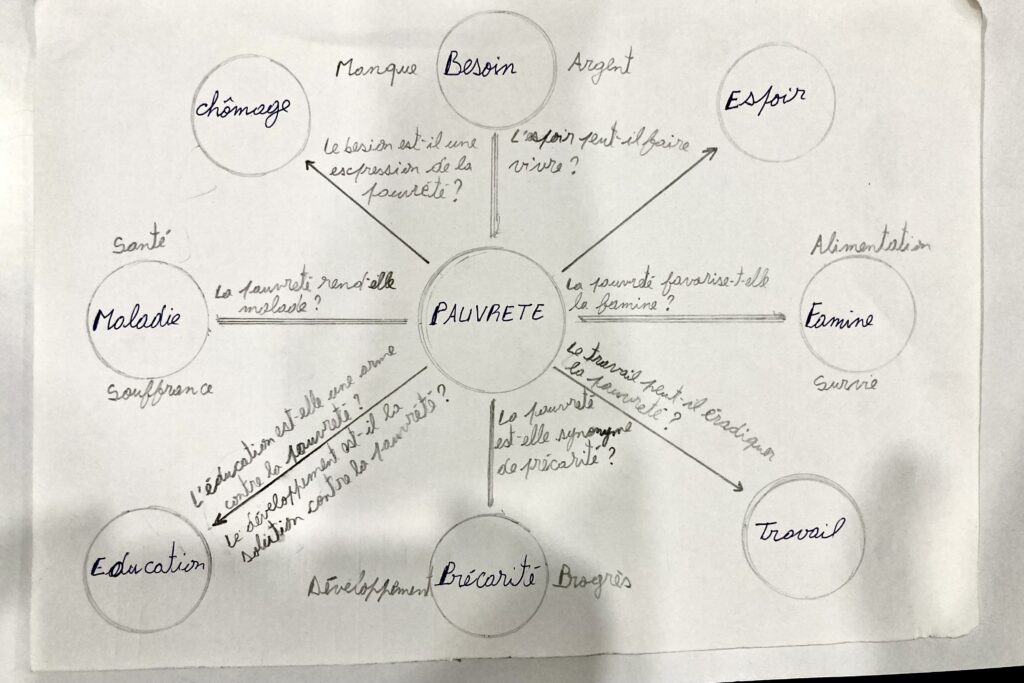

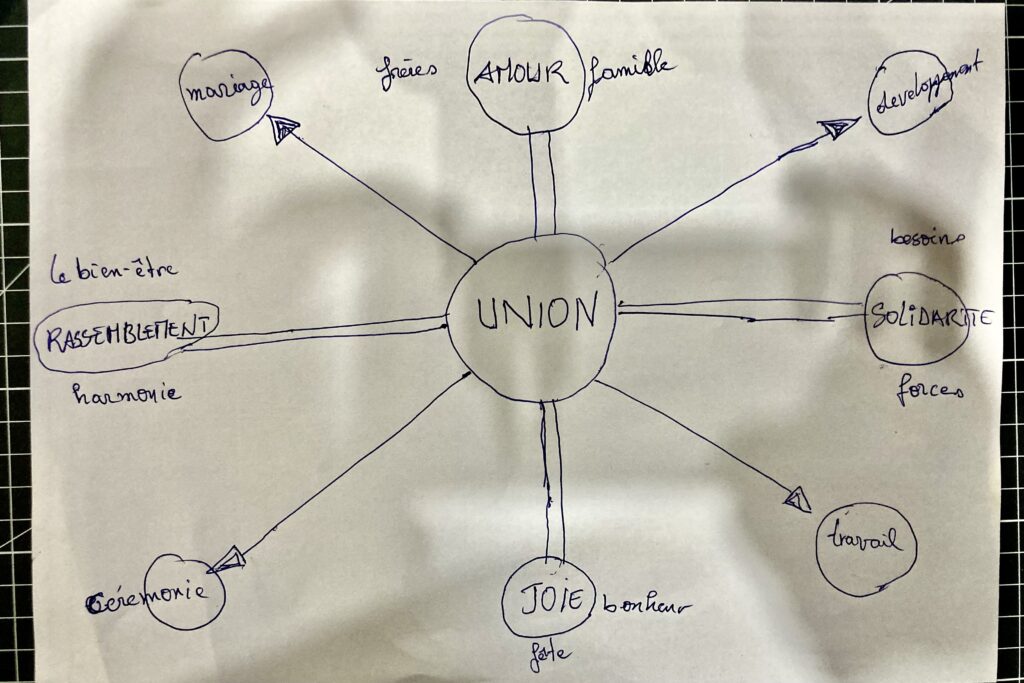

The curriculum was structured into ten three-hour sessions using a modified version of the Community of Philosophical Inquiry (CPI). The emphasis was on learning to think through the challenges of intersectionality in an engaging and FUN way! So, I made sure to include various game-like activities like the ‘back card game,’ the ‘could be GRATER’ and mindmaps.

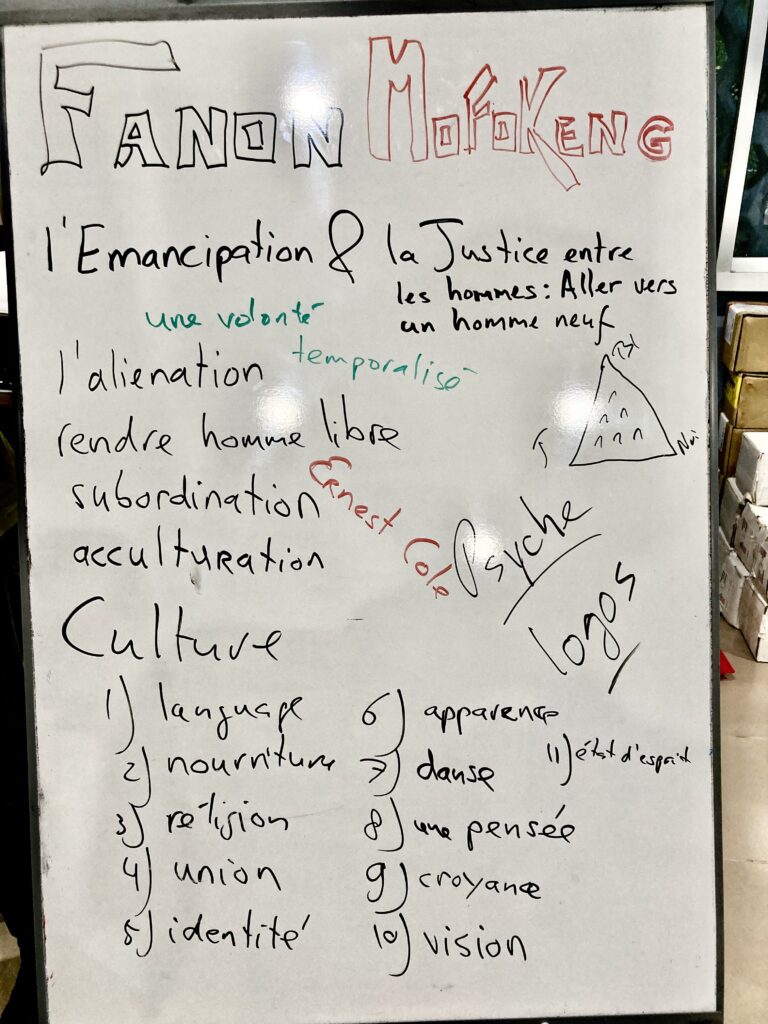

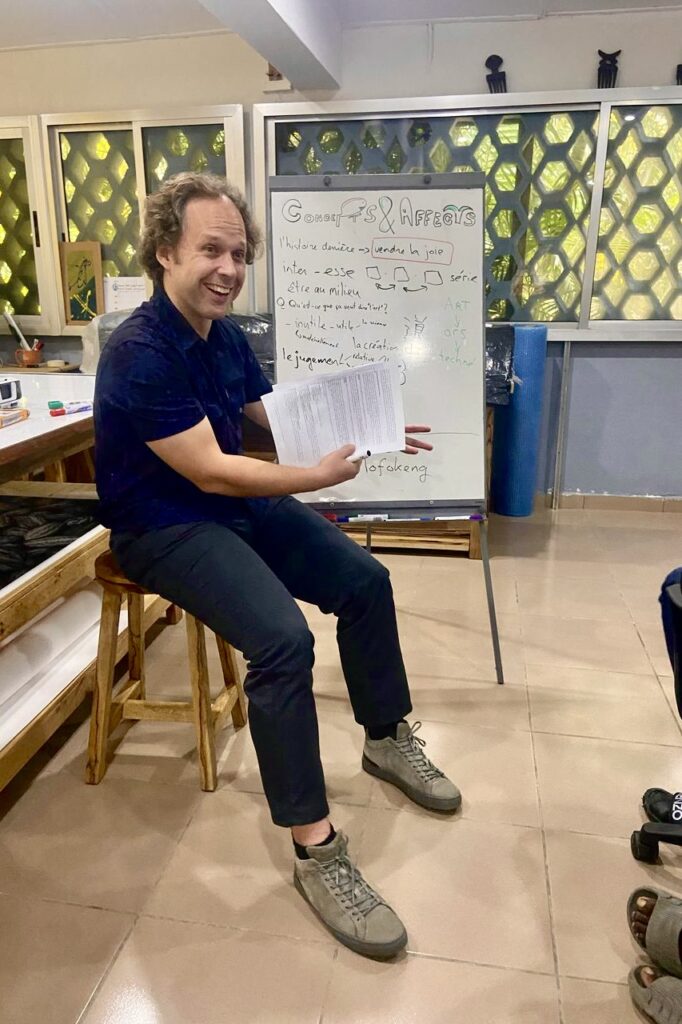

In each session, we examined key concepts such as Power, Control, Equity, Colonialism, Love, and Culture by linking them to iconic photographic works. For example, we paired the writings of Frantz Fanon with the haunting images of Santu Mofokeng. We delved into how the photographer’s eye can capture not just a scene but the lingering traces of colonial history and its effects on contemporary society.

I introduced conceptual-affective tools inspired by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari to help the photographers think about what a concept “could be”—a way of pushing beyond what is given and opening up the space for creative interpretation. This encouraged them to see, feel, and express the layers of human experience in their images. However, this also led to the question of why a series of images can be more powerful than a single image in showing these problems.

For that reason, I introduced the question of why series matter, like photo essays in contrast to single images. I used the Herman Grid to introduce this.

I asked them how the Herman Grid relates to creating a series and seeing the space in between images doing their work. We don’t see single dots anymore, but our brain fills up the in-between to create a smoother connection between dots. It helps connect them. We look for connection but can’t always see it. Your work can show connection through a series that spectators otherwise would not be able to see.

We saw that concepts and affects bring series to life. They make your art more powerful.

Philosophy, Artists & Intersectional Sensibility

If you would like to know more about this, please do not hesitate to reach out and contact us. Let us empower more artists around the world!