A philosopher is someone who seeks to be wise. A wise person, in turn, is someone who directs his/her own beliefs and behaviour in ways that can be reasonably justified, i.e., justified according to the best of all competing reasons. In this way, a wise person is someone who is prepared to take responsibility for his or her actions and, thus, in that sense, recognizes that what s/he thinks, how s/he acts, and what s/he says contributes to the person s/he is becoming. This sense of self-legislation (or self-empowerment) can powerfully contribute to a stable sense of personal well-being and, hopefully, to the well-being of her/his community.

At the same time, it nurtures important social habits and dispositions, such as social communication and inclusion, reasonable disagreement exploration, and cooperative and constructive behavior.

The goal of THE THINKING PLAYGROUND is to help campers become wise people by creating an environment conducive to thinking carefully about reasons and engaging in authentic philosophical dialogue. This is done in several ways.

Community of Philosophical Inquiry

First and foremost, throughout the day, children will engage in a number of Communities of Philosophical Inquiry (CPIs)—a pedagogical tool, first made famous by Matthew Lipman, the founding director of The Institute for the Advancement of Philosophy for Children (IAPC), and one practiced throughout the world (see The International Council for Philosophical Inquiry with Children (ICPIC) (of which the co-host for THE THINKING PLAYGROUND CAMPS, The Vancouver Institute of Philosophy for Children (VIP4C), is a member).

A THINKING PLAYGROUND CPI is one in which both campers and several counsellors come together, under the facilitation tutelage of one of the counsellors, in order to inquire about an issue of importance with the goal of elucidating the most reasonable position with regard to the matter at hand. The goal is that, in the process, inquirers learn the importance of being able to articulate their reasons for holding a given view, listening to the points of view of others, subjecting their own reasoning and that of others to potential counter-examples and, in so doing, learn the difference between good and poor reasoning, the power of being able to change one’s mind as a function of following reasons where they lead, and, in general, experience the thrill of building more sustainable positions in cooperation, i.e., in community with others.

Thinking is essential:

- for constructive communication

- for healthy mental and emotional development

- for dealing with the pressures of life

- for good judgement

- for self-growth

Thinking is learning:

- to listen to each other

- to ask interesting questions

- how to make connections between ideas

- how to build on each other’s ideas

- what counts as a reason

- to express your reasons

- to think before you act

Ethics

As with any other skill, learning how to live wisely requires practice. It is for this reason that the camp activities and communities of inquiry relate to the sorts of values and fundamental issues that all humans must negotiate, i.e., philosophical issues. For self-conscious beings, practice in living wisely can be done by imaginatively engaging with stories, games, and role play. With regard to “value-education,” however, THE THINKING PLAYGROUND is particularly sensitive to the danger that these sorts of discussions can easily swerve toward the abstract and “instructively” politically correct; i.e., that such activities can implicitly send the message loud and clear that kids are supposed to be polite, kind, brave, or whatever. To the degree that they do this, they short-circuit the kind of thinking that is needed for children to make the values their own and to successfully navigate real-world, complicated situations with conflicting demands. It is for this reason that THE THINKING PLAYGROUND curriculum is meticulously constructed so that value-inquiry is genuine inquiry, i.e., value issues are always rooted in contexts that require campers and counsellors alike to agonize over which values trump others in any given situation. The intent is that such exposure will ramp up the life-long practice of weaving together, with the tinsel strength of reasoning, a value-tapestry that is genuine, predictable, and stably their own.

Swinging with Questions

Aside from the issue under discussion, an important aspect that often determines whether or not a community of inquiry is successful is the quality of the actual question on which it focuses. This mirrors the fact that successful thinking is, as well, frequently a function of the degree to which it is embedded in a quality question. With regard to thinking that informs wisdom, it is critical that the question be sufficiently relevant that it is evident how it might reflect on campers’ own lives and interests; this ensures not only that campers become genuinely invested in the process of inquiry, but also that thinking done in camp begins to seep into their own lives. It is also crucial that the question is framed in such a way that inquirers can readily see the possibility of responding either “yes” or “no,” i.e., that this is a “real,” or what we sometimes refer to as a “trapeze” question—one that provides the swing of genuine thought. It is also important that the question be sufficiently precise that it provides an anchor for the inquiry, i.e., prevents discussion chaos, as well as being important for the potential to guide action, i.e., only a precise vision can elicit a clear response. It is for these reasons that THE THINKING PLAYGROUND curriculum construction is informed by the potential for activities to generate good questions, to help children recognize good questions and to ask good questions, including questions that the curriculum designers may not have thought of themselves.

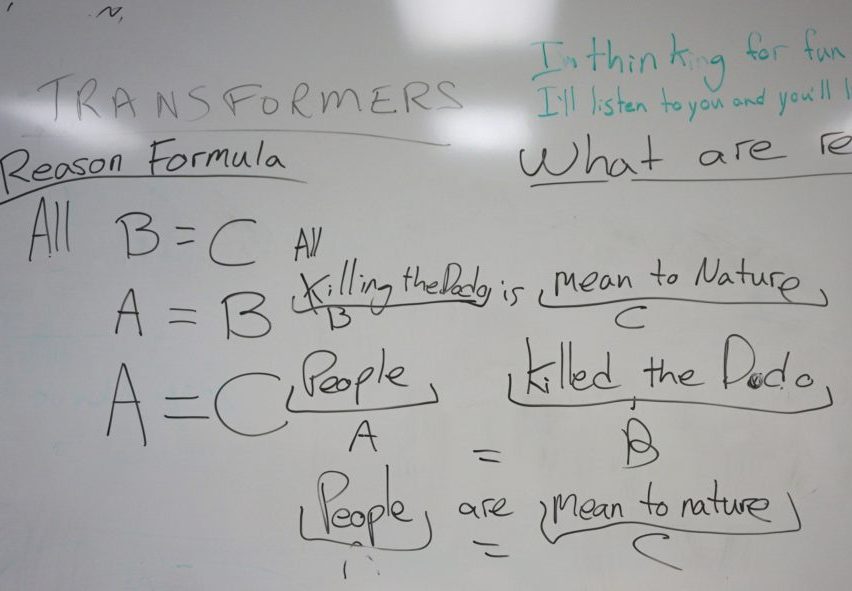

Logic

While trying to ensure that the overall atmosphere is FUN, FUN, FUN, we have come to the conclusion that a minimum amount of direct instruction is imperative if the children are to maximally benefit from this philosophical experience. Among the topics of direct instruction are:

- Learning that good thinking requires a quality question.

- Learning that the merit of any position cannot be estimated unless it is backed by reasons.

Learning that every reason is accompanied by a “sneaky silent reason.”

- Learning that the strength of any reason is always a function of the degree to which it is vulnerable to counter-example.

- Learning that the strength of any position depends on the merits of competing positions and that therefore listening to opposing views is essential if one is to be a good thinker.

- Feeling comfortable about changing one’s mind in the face of stronger competing evidence.

Tinker Thinkers Book

Beginning in the summer of 2016, all campers eligible to receive (upon request) a book entitled Tinker Thinkers that outlines, in simple format, many of the moves described above. Hopefully, this book will provide an opportunity for campers to teach their parents what good reasoning is all about, and so further solidify their own understanding.

Bonding & Community

Learning any new skill, including thinking, is risky, as anyone who has belly flopped in front of laughing peers while trying a new dive can attest to. It is for that reason that counsellors work hard to create real bonds with all the campers so that they feel cherished and safe. It is in this sort of environment that campers are more liable to speak up and try out what they really think about the issue under discussion. It is also in this sort of environment that campers are more able to tolerate the realization that their first attempts at reasoning through a situation may not be very strong. Learning to leave behind positions that cannot be supported by good reasons is difficult for anyone, as it is often viewed as an admission of being dumb. Ultimately, we all must learn that discarding (relatively) unreasonable positions, i.e., having a robust capacity to change one’s mind in face of more compelling arguments, is the cardinal mark of a good thinker. A safe, caring environment is one in which this capacity is more likely to be acquired.

Role-Modeling

Counsellor role-modeling, as individuals and as team members, is another way in which THE THINKING PLAYGROUND tries to instill in campers the conviction that good thinking is something to which they ought to aspire. Though counsellors serve as role models probably primarily because they are such “fun,” somewhat goofy, and always engaged, that these role models clearly cherish good thinking is something that campers cannot help but notice. As well, that these role models care for one another and yet model moves of good thinking that in ordinary every-day life are sometimes viewed as negative (e.g., suggesting alternative ways of looking at an issue, pointing out faulting reasoning, changing one’s mind in the face of more compelling arguments) models the important understanding that reasoning must be viewed as, in a sense, “non-personal,” i.e., my “negative” view of your argument is not a “negative” view of you. I can love and care for you and still engage in a robust reasoning engagement with you.

Interpersonal Environment

A rich, thick interpersonal environment is maintained throughout the camp in the sense that we never allow our numbers to drop below 1 counsellor to 5 campers, and, indeed, try hard to maintain the level at a minimum of 1:4. Campers are thus never very far from the sight and earshot of a counsellor, and so counsellors and maybe only one or two campers are able to engage in many impromptu informal COI’s. It is in this way that we hope to send the message that this sort of thinking, i.e., looking at alternative views, judging the merits of reasons behind each position, thinking cooperatively, etc., is ultimately a “way of life,” not merely a camp experience.

Counsellor Training

Counsellor preparation is essential if any of the above goals are to be maintained. Thus, all counsellors are required to have a significant exposure to academic philosophy (which ranges from the bachelor to the Ph.D. level). Counsellors also attend bi-monthly in-person seminars and workshops, beginning in the fall before camp starts, under the supervision of the Director and Assistant Director (both university philosophy professors), that focus specifically on the intricacies Philosophy for Children (P4C) in general, and the curriculum in particular. As well, there are constant on-line discussions as to how the best possible experience can be provided to the campers.

Curriculum

The Curriculum, though it is informed by university critical-thinking education strategies, as well as the myriad of strategies employed throughout the P4C community world-wide, is an on-going struggle—and of this we are proud. That we, as a community of directors and counsellors, are continuously altering, fine-tuning, throwing out, experimenting, changing styles, etc., is the life blood that nourishes our committed passion to give our best to the campers, so that they, too, leave us with a vision of striving to be the best that they can be. That we are often torn between our “educational” and “fun” mandates just renews our commitment to the unique challenge of trying to combine experiences that are often considered disparate. Nonetheless, it is our foundational goal that THE THINKING PLAYGROUND experience is such that campers leave us with a view that thinking actually IS fun—an attitude which we believe is crucial to underpinning a life-long dedication to the hard work of thinking one’s way to a good life. A goal of this magnitude inevitably demands an ever-evolving curriculum and the commitment of an amazing team.

Further Theoretical Background by our Team

For further theoretical background, please feel free to peruse any related articles written by our director. As well, literally thousands of articles on Philosophy for Children (P4C) can be found on the web. We include on our website an article by Dr. Gardner written specifically for parents entitled “What Would Socrates Say to Mrs. Smith?” published in the British journal Philosophy Now, issue 84, May/June 2011, pp. 24-26, as well as an article co-written with Daniel Anderson, published in the 2015 edition of Mind, Culture, and Activity, entitled “Authenticity: It Should And Can Be Nurtured” and a chapter in the (2017) Routledge handbook of Philosophy for Children entitled “Questioning the Question: A hermeneutical perspective on the ‘art of questioning’ in a community of philosophical inquiry” by our Educational Director Dr. Arthur Wolf and co-written with Dr. Barbara Weber. Dr. Arthur Wolf has also written an essay entitled ‘Existential Urgency: Towards a Provocation to Thinking Different,’ which combines a reading of Heidegger’s provocation to think and Merleau-Ponty’s concept of embodiment to reconceptualize thinking as embodied practice. In addition, his essay entitled ‘Affect and Philosophical Inquiry with Children’ was awarded the 2022 essay prize by the International Council of Philosophical Inquiry with Children (ICPIC) and which will be published in the journal Childhood & Philosophy. In 2018 he also co-wrote an article (see the media page) and children’s book with Dr. Gardner.